Detroit’s Healthcare History: A Story of Rise and Fall

Hospitals in detroit that have closed tell a powerful story of a city’s change through decades of economic, social, and demographic change. Detroit once boasted numerous community hospitals serving diverse neighborhoods, but many have shuttered their doors forever, leaving behind empty buildings and memories of the care they once provided.

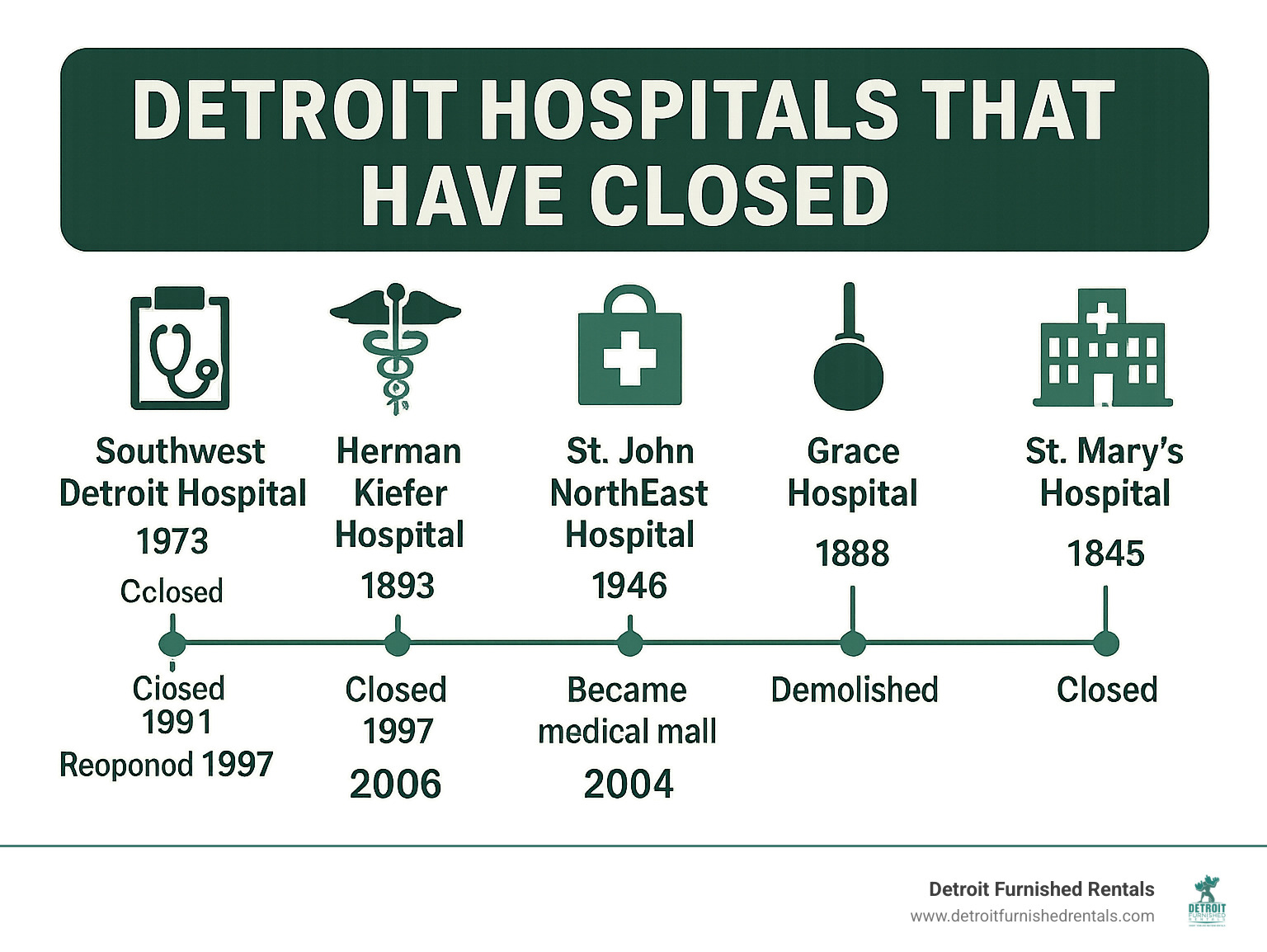

Major Detroit Hospitals That Have Closed:

- Southwest Detroit Hospital (1973-1991, reopened 1997-2006) – Now slated to become Detroit City FC stadium

- Herman Kiefer Hospital (1893-2013) – Former public health complex, closed and offered for sale

- St. John NorthEast Hospital (1946-2004) – Became medical mall, owner filed bankruptcy in 2023

- Grace Hospital (1888-1979) – Demolished for parking lot, where Harry Houdini died in 1926

- St. Mary’s Hospital (1845-1987) – Detroit’s first hospital, demolished in 1990

- Detroit Hope Hospital (closed 2010) – Last minority-owned hospital in Detroit

These closures reflect broader challenges including Detroit’s population decline from over 1.8 million in 1950 to under 700,000 today, economic hardship, and the shift toward larger suburban medical centers. Some hospitals faced specific issues like financial mismanagement – Southwest Detroit Hospital’s second operator misused $15 million in taxpayer funds before closure.

The impact extends beyond healthcare access. When Southwest Detroit Hospital closed in 1991, it eliminated hundreds of jobs and left southwest Detroit’s 200,000 residents with fewer medical options. Similarly, Herman Kiefer Hospital’s 2013 closure ended over a century of public health services.

I’m Sean Swain, and through my work with Detroit Furnished Rentals, I’ve witnessed how hospitals in detroit that have closed have shaped neighborhoods where our guests stay. My experience hosting traveling nurses and healthcare professionals has given me unique insight into Detroit’s evolving medical landscape and the stories behind these shuttered institutions.

Learn more about hospitals in detroit that have closed:

The Changing Face of Healthcare in Detroit

Detroit’s healthcare story mirrors the city’s own journey through triumph and struggle. When the Motor City was booming in the mid-1900s, neighborhood hospitals thrived alongside busy communities. But as Detroit’s population dropped from over 1.8 million to under 700,000, these same hospitals found themselves fighting for survival.

The exodus to the suburbs hit Detroit’s hospitals particularly hard. Families who once lived within walking distance of their community hospital suddenly found themselves driving to newer facilities outside the city. Meanwhile, those who remained often faced economic hardships that made healthcare less accessible.

Racial segregation added another painful layer to Detroit’s healthcare challenges. For decades, Black patients were turned away from major hospitals, forcing communities to create their own medical networks with far fewer resources. Even when federal programs like Hill-Burton promised to expand hospital construction, they didn’t always tear down the walls of inequality that divided care.

As the city’s economic foundation crumbled, smaller hospitals couldn’t keep up with rising costs and shrinking patient numbers. Large hospital systems like DMC Detroit Medical Center and Henry Ford Hospital had the resources to weather these storms and even expand their reach. But for community hospitals already stretched thin, these changes often meant closing their doors forever.

The financial pressure was relentless. Insurance companies became more demanding, federal funding became less reliable, and competition grew fiercer. Many hospitals in detroit that have closed simply couldn’t adapt fast enough to survive.

The Shift from Community Care to Corporate Health Systems

The change from cozy neighborhood hospitals to massive corporate health systems changed everything about how Detroiters received care. Community hospitals had been like family – they knew your name, understood your neighborhood, and provided care that felt personal and accessible.

But these smaller hospitals faced battles they couldn’t win alone. Insurance challenges became overwhelming as billing grew more complex and negotiations with powerful insurance companies required teams of specialists. Many community hospitals simply didn’t have the staff or expertise to handle these administrative nightmares.

Federal funding changes made things worse. While programs like Hill-Burton had initially helped build hospitals, shifting policies left many facilities scrambling to stay financially stable without government support.

Ironically, desegregation – while absolutely necessary for equality – created unexpected challenges for historically Black hospitals. When the Civil Rights Act of 1964 opened previously whites-only hospitals to all patients, Black-owned hospitals suddenly lost many of their patients to larger, better-funded competitors. The History of black hospitals explained reveals how this civil rights victory had complex consequences for Black medical institutions.

Competition for patients became brutal. With Detroit’s population shrinking, hospitals found themselves fighting over fewer residents. Many patients chose newer suburban facilities when they could, leaving urban hospitals struggling to fill beds and pay bills.

This perfect storm of challenges explains why so many community hospitals couldn’t survive the transition to corporate-dominated healthcare. The personal touch that made them special simply wasn’t enough to overcome the economic realities of modern medicine.

A Tour of Hospitals in Detroit That Have Closed

Walking through Detroit today, you’ll pass empty lots and repurposed buildings that once housed thriving hospitals. Each of these hospitals in detroit that have closed has a story worth telling – stories of hope, community service, financial struggles, and sometimes remarkable second chances.

Let me take you on a journey through some of the most significant closures that shaped Detroit’s healthcare landscape. These aren’t just statistics or empty buildings; they’re places where babies were born, lives were saved, and communities gathered during their most vulnerable moments.

Southwest Detroit Hospital: From Community Guide to Soccer Pitch

The Southwest Detroit Hospital story reads like a novel with dramatic highs and crushing lows. When it opened in 1973, this wasn’t just another hospital – it was a symbol of progress and equality in a city still struggling with racial divisions.

Born from the merger of four smaller hospitals – Boulevard General, Burton Mercy, Delray General, and Trumbull General – Southwest Detroit Hospital was designed to serve 200,000 residents in an underserved area. What made it truly special was its groundbreaking commitment to diversity. This was the first Detroit hospital to hire and credential African American doctors and nurses, a move that opened doors previously slammed shut by discrimination.

The five-story, 250-bed facility cost $21 million to build (that’s about $175 million today). The funding came from impressive sources: the United Foundation, federal Hill-Burton programs, and major foundations like Kellogg and Kresge. When Mayor Coleman A. Young cut the ribbon in October 1974, the community had every reason to celebrate.

But success proved elusive. After just 17 years, Southwest Detroit Hospital filed for bankruptcy in 1991. The closure followed a troubled period marked by legal controversies and accusations of unethical practices. The building sat empty for years, becoming a haunting reminder of dashed hopes.

Hope returned in 1996 when new owners purchased the building for $1.5 million and reopened it as United Community Hospital in 1997. They invested around $6 million in renovations, but this second chance was even shorter-lived. The new operators, Ultimed, faced serious accusations of financial misconduct, including misusing nearly $15 million in taxpayer funds for personal luxuries. The state seized the hospital in 2006, and it closed for good that January.

For nearly two decades, the abandoned hospital became an urban explorer’s destination, its empty halls echoing with memories of better times. But here’s where the story takes an amazing turn: Detroit City Football Club acquired the site for redevelopment into a soccer-specific stadium, expected to open before the 2027 season. It’s a perfect example of Detroit’s resilience – changing a symbol of decay into a vibrant community asset. You can read more about this exciting Redevelopment by Detroit City FC and explore its full history at Southwest Hospital | Historic Detroit.

Herman Kiefer Hospital: A Public Health Fortress

If Southwest Detroit Hospital was about community care, Herman Kiefer Hospital was Detroit’s fortress against disease. This massive complex, dating back to 1893, began as something quite specialized – a clinic dedicated to fighting contagious diseases like smallpox and tuberculosis.

The hospital was strategically placed on Detroit’s northern outskirts to isolate patients with highly communicable illnesses. Named after Herman Kiefer, a German immigrant physician and civil rights activist, the facility represented Detroit’s early commitment to public health. His son, Dr. Guy Kiefer, was instrumental in its establishment.

The first buildings opened in 1911, designed by renowned architect George D. Mason. But the real expansion came in the 1920s when voters approved a $3 million bond. This brought in another architectural legend – Albert Kahn – who designed additional pavilions and a powerhouse. The magnificent main building opened in December 1928.

At its peak, Herman Kiefer was truly massive – 1,265 beds across six pavilions and the main building. It was Detroit’s public health headquarters, handling everything from disease prevention to vaccinations to treatment of the city’s most challenging medical cases.

But success in public health eventually made Herman Kiefer less necessary. As vaccines and effective treatments eliminated many infectious diseases, the specialized facilities sat underused. Pavilions 3 and 5 were demolished in 1964 to make room for Sanders Elementary School. The hospital tried to adapt in the late 1970s and early ’80s, serving as a general hospital, clinic, and drug treatment center.

In its final chapter, Herman Kiefer became home to the city’s Department of Health and Human Services in 2011. The city invested hundreds of thousands in renovations, but this period was troubled by reports of unsanitary conditions and financial mismanagement. The department shut down in March 2012, and the entire Herman Kiefer complex closed on October 1, 2013. The city put the building up for sale, and its future remains uncertain.

The scale and history of Herman Kiefer remind us how much Detroit’s public health needs have evolved – quite different from modern facilities like Detroit Receiving Hospital that serve the city today.

St. John NorthEast (Holy Cross) Hospital: A Community’s Loss

Sometimes the most heartbreaking closures are the ones that happen gradually. St. John NorthEast Hospital, originally Holy Cross Hospital when it opened in 1946, served northeast Detroit’s community for decades as a solid 295-bed facility.

When St. John Health purchased it in 1996 and rebranded it as St. John NorthEast Hospital, there was hope that the larger system could sustain what the independent hospital couldn’t. But dwindling patient counts told a different story. By 2004, St. John Health made the difficult decision to close primary hospital services.

What happened next was creative, if ultimately unsuccessful. Instead of abandoning the building entirely, it continued operating as a “medical mall” – hosting various clinics, social services, and an urgent care center. This model kept some healthcare services in the community even without inpatient beds. As recently as 2020, the Conner Creek Health Center operating within the facility had nearly a dozen tenants.

But the medical mall concept couldn’t overcome the fundamental economics. The owner, Conner Creek Center, filed for bankruptcy on September 22, 2023. The building and its 13.3-acre property went to auction with bidding starting at just $400,000 in June 2024.

There’s a silver lining to this story, though. About 3 acres of the parking lot were sold in 2023 for the Benjamin O. Davis Veterans Village, a 50-unit housing project for low-income military veterans. The project faced a $1.6 million budget shortfall due to the hospital owner’s bankruptcy, but the city stepped up with $1.4 million to keep this important community project moving forward. You can learn more about this inspiring Benjamin O. Davis Veterans Village.

The St. John NorthEast story shows how even large systems like Ascension St. John’s Hospital face tough decisions about which facilities to maintain in a changing healthcare landscape.

Other Notable hospitals in detroit that have closed

The three hospitals we’ve explored in detail represent just the tip of the iceberg. Detroit’s medical history includes many other significant closures, each with its own compelling story.

Grace Hospital holds a special place in both medical history and popular culture. Opening on December 7, 1888, it was named after Grace McMillan Jarvis, daughter of industrialist James McMillan. By 1964, it had grown to become Michigan’s second-largest nonprofit hospital. But Grace Hospital’s most famous moment came on Halloween 1926, when legendary magician Harry Houdini died in Room 401 from sepsis caused by acute appendicitis. The original building was demolished in 1979 for a parking lot, though Grace Hospital’s legacy continued when it merged into the Detroit Medical Center in 1985.

Even older was St. Mary’s Hospital, Detroit’s very first hospital, established by the Sisters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul on June 9, 1845. Think about that – Detroit’s population was only around 11,000 people then! Initially called St. Vincent’s Hospital, it moved to a larger Clinton Street building in 1850 with space for 150 patients. St. Mary’s served as a military hospital during both the Civil and Spanish-American Wars. After becoming Detroit Memorial Hospital in 1948, it opened Michigan’s first multiple sclerosis center in 1950. The hospital closed in 1987 and was demolished in February 1990. You can read more about St. Mary’s Hospital Detroit Michigan.

Perhaps most poignant was the closure of Detroit Hope Hospital in January 2010 – the last minority-owned hospital in Detroit. This facility had gone through many iterations, from Park Community Hospital (founded by Dr. David Friedman to serve Black patients denied care elsewhere) to New Center Hospital, Renaissance Hospital, and finally Detroit Hope. Despite Dr. Dass investing nearly $6.6 million in improvements, the hospital battled constant financial and regulatory challenges. It lost Medicare accreditation in 2009 and had its licenses revoked for violations including staffing shortages. The closure marked the end of an era for community-focused healthcare serving Detroit’s most vulnerable populations.

These hospitals in detroit that have closed remind us that behind every closure was a community that lost not just healthcare access, but jobs, neighborhood identity, and often hope itself. Yet Detroit’s story continues to evolve, with new facilities rising and old sites finding new purposes.

The Community Impact of Vanishing Hospitals

When hospitals in detroit that have closed their doors forever, the ripple effects spread far beyond empty buildings and shuttered emergency rooms. These closures have fundamentally reshaped entire neighborhoods, creating challenges that residents still face today.

The most immediate impact is the creation of healthcare deserts – areas where residents must travel significant distances to reach basic medical care. When Southwest Detroit Hospital closed in 2006, for example, the 200,000 residents of southwest Detroit suddenly found themselves with fewer nearby options for emergency care, routine checkups, and specialized treatment. For families without reliable transportation, what used to be a quick trip to the neighborhood hospital became an all-day journey across town.

This distance isn’t just inconvenient – it can be dangerous. Longer emergency response times mean ambulances must travel farther to reach open emergency rooms, and those extra minutes can mean the difference between life and death. When Herman Kiefer Hospital closed in 2013, emergency services had to reroute to facilities that were often already operating at capacity.

The job losses from hospital closures have been staggering. Each hospital employed hundreds of people – doctors, nurses, technicians, cafeteria workers, security guards, and administrative staff. When Grace Hospital closed in 1979, it wasn’t just medical professionals who lost their jobs. The local restaurants, gas stations, and shops that relied on hospital employees as regular customers also felt the economic blow.

Perhaps most heartbreaking is the loss of neighborhood identity that comes with hospital closures. For decades, these institutions served as anchor points for their communities. They were places where babies were born, where families gathered during medical crises, and where neighbors worked side by side. When St. Mary’s Hospital – Detroit’s very first hospital – was demolished in 1990, it took with it nearly 150 years of community history.

The impact on vulnerable populations has been particularly severe. Elderly residents who relied on nearby hospitals for regular care now face difficult journeys to distant facilities. Low-income families struggle with transportation costs and time off work for medical appointments that used to be just down the street. The closure of Detroit Hope Hospital in 2010 was especially significant because it was the last minority-owned hospital in the city, ending an era of community-focused care for underserved populations.

Today’s healthcare landscape looks dramatically different from the Detroit of the 1950s and 60s, when neighborhood hospitals dotted the city. Understanding how we got here helps us appreciate both the challenges and the opportunities ahead. For those navigating Detroit’s current healthcare system, whether as residents or visiting professionals, resources like Metropolitan Detroit Area Hospital Services provide valuable guidance in this transformed landscape.

Frequently Asked Questions about Detroit’s Closed Hospitals

People often ask me about Detroit’s hospital closures when they’re staying with us, especially healthcare professionals who are curious about the city’s medical history. These questions come up regularly, so I thought I’d share some answers.

Why did so many hospitals in Detroit close?

The story behind why so many hospitals in detroit that have closed is really a perfect storm of challenges that hit the city over several decades. The biggest factor was Detroit’s massive population drop – we went from over 1.8 million people in 1950 to under 700,000 today. When you lose that many potential patients, hospitals simply can’t sustain themselves.

The economic troubles that followed made things even worse. High unemployment meant fewer people had health insurance, and those who did often couldn’t afford their co-pays or deductibles. Hospitals found themselves treating more uninsured patients while receiving less revenue.

Financial mismanagement played a huge role in specific cases too. Southwest Detroit Hospital’s operators misused $15 million in taxpayer funds, while Detroit Hope Hospital struggled with questionable expenses and regulatory violations. These weren’t just business decisions gone wrong – they were often cases of poor leadership that directly harmed community healthcare.

The rise of large suburban medical centers also drew patients away from city hospitals. People with cars and insurance options often chose newer facilities with more services, leaving urban hospitals with shrinking patient bases. Add in the shift toward outpatient care and stricter federal regulations, and many smaller community hospitals just couldn’t keep up.

What happened to the old hospital buildings?

The fate of these abandoned hospital buildings tells its own fascinating story about Detroit’s journey. Some buildings, like Grace Hospital and St. Mary’s Hospital, were simply torn down. Grace Hospital became a parking lot, while St. Mary’s site sat empty for years before being considered for various projects.

Southwest Detroit Hospital had perhaps the most interesting journey. After closing in 2006, it sat empty for nearly two decades, becoming a popular spot for urban explorers drawn to its decaying halls. But now it’s getting a second life as the future home of Detroit City FC’s soccer stadium – a perfect example of how Detroit transforms its past into something new.

Herman Kiefer Hospital remains largely intact but vacant since 2013, with the city still looking for buyers or developers willing to take on such a massive complex. Meanwhile, St. John NorthEast Hospital tried to reinvent itself as a medical mall after closing as a full hospital, housing various clinics and services until its owner filed for bankruptcy in 2023.

The most heartwarming change might be happening at St. John NorthEast, where part of the property is becoming the Benjamin O. Davis Veterans Village – 50 units of housing for veterans who need it most.

Are any of Detroit’s historic hospitals still in operation?

Absolutely! While we’ve lost many hospitals over the years, several historic institutions continue to thrive and serve our community. Henry Ford Hospital, founded by the automotive pioneer himself, remains one of Detroit’s leading medical centers, known for groundbreaking research and excellent patient care.

The Detroit Medical Center, which includes facilities like DMC Harper University Hospital, continues to be a major healthcare provider in the city. These surviving hospitals have managed to adapt, expand, and modernize over the decades, ensuring they remain relevant in today’s healthcare landscape.

What’s remarkable about these surviving institutions is how they’ve evolved while maintaining their commitment to serving Detroit residents. They’ve invested in new technology, expanded their services, and found ways to remain financially viable even as the city around them changed dramatically.

Conclusion: Remembering the Past, Building the Future

The stories of hospitals in detroit that have closed remind us that endings can become new beginnings. What started as a tale of shuttered doors and empty buildings is slowly changing into something hopeful and inspiring. Detroit has always been a city that knows how to reinvent itself, and these former hospital sites are becoming powerful examples of that resilience.

Looking at that rendering of the new Detroit City FC stadium rising where Southwest Detroit Hospital once stood, it’s hard not to feel excited about the possibilities. Where urban explorers once wandered through decaying hallways, families will soon cheer for their team. Where patients once received care, a different kind of community healing will take place through sports and shared experiences.

The same spirit of renewal is happening across the city. The Benjamin O. Davis Veterans Village, built on part of the old St. John NorthEast Hospital property, shows how these sites can serve their communities in new ways. Instead of treating illness, they’re now addressing homelessness and supporting our veterans.

These changes don’t erase the important history of these places. Herman Kiefer Hospital’s century-long fight against infectious diseases, Southwest Detroit Hospital’s groundbreaking role in integrating healthcare, Grace Hospital’s connection to Harry Houdini – these stories matter. They’re part of Detroit’s fabric, woven into the neighborhoods where people still live and work today.

Historical preservation doesn’t always mean keeping buildings standing. Sometimes it means remembering the stories, honoring the people who worked and were cared for in these places, and finding ways to serve the community that build on that legacy.

For visitors exploring Detroit’s rich medical history, or traveling nurses and healthcare professionals working in the city’s current hospitals, understanding these stories adds depth to the Detroit experience. The city’s healthcare landscape continues to evolve, with strong institutions like those you’ll find in our Area Guide: Detroit Hospitals carrying forward the mission of caring for this community.

Whether you’re here to work in Detroit’s healthcare system, explore its history, or witness its ongoing change, finding comfortable accommodations makes all the difference. We understand that Detroit is more than just a place to stay – it’s a city with stories to tell, and we’re here to help you become part of that continuing narrative.